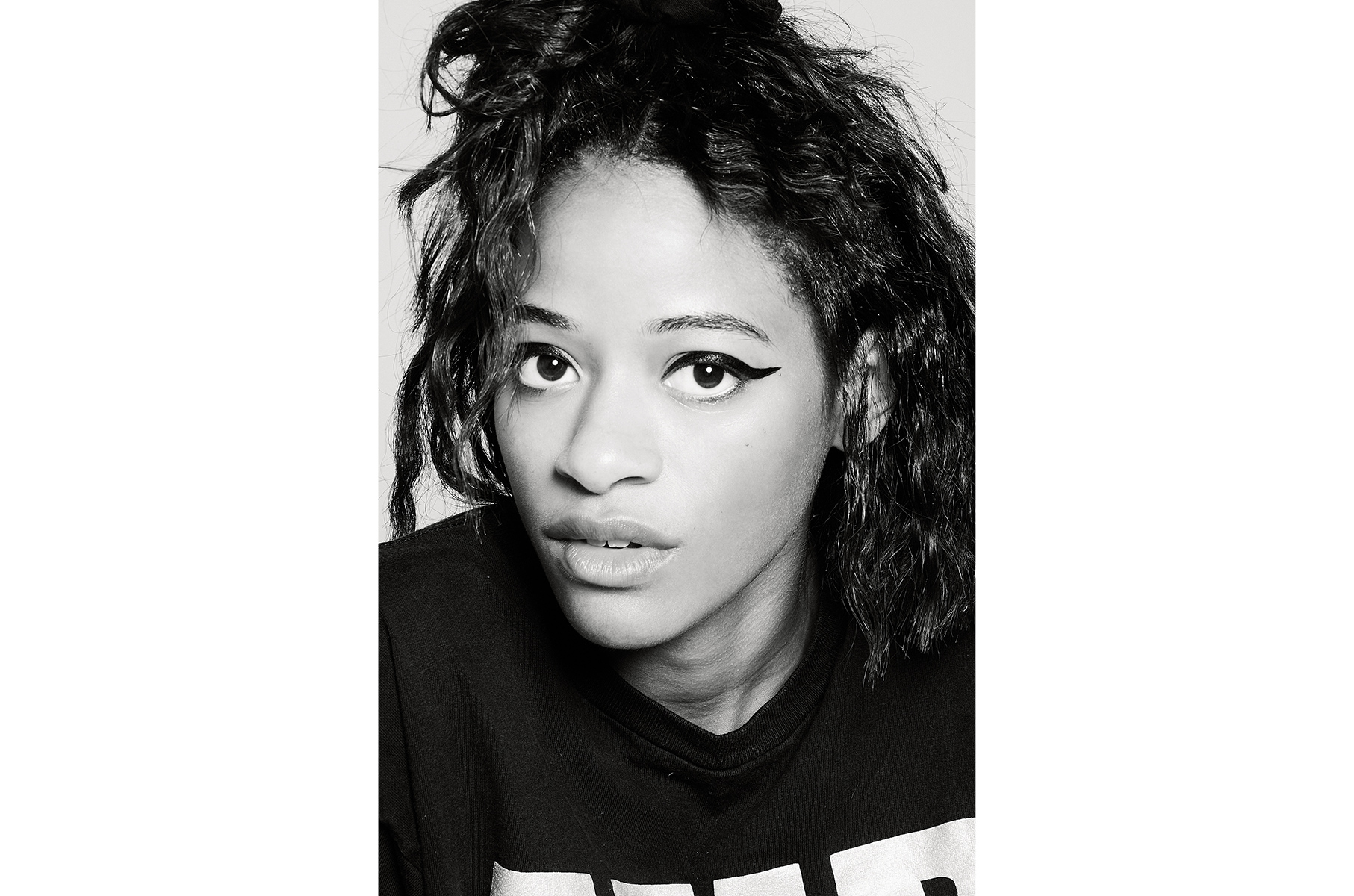

Kilo Kish

Interview by Aly Wicker

Images by Jan-Willem Dikkers

“I can be satisfied with the fact that I achieved what I wanted,

but there’s always another level.”

— Kilo Kish

Kilo Kish

Kilo Kish, the artistic moniker of Lakisha Robinson, is an American singer, rapper, visual artist, and fashion designer based in Los Angeles. She released her debut album, Reflections in Real Time, in 2016 and has just released her newest EP, Mothe (2018). Kish has collaborated with likes of Vince Staples, Gorillaz, A$AP Rocky, The Internet and Childish Gambino. Her new fashion brand, AGGY!, premiered at the 2018 ComplexCon.

An architecture dropout turned fashion major, Kilo Kish picked up music as yet another creative outlet on top of design and visual art. She has since released a full-length debut album Reflections in Real Time (2016) and collaborated with musicians such as Childish Gambino, Vince Staples, The Internet and Gorillaz. Her newest EP, Mothe, is not-so-subtly interested in metamorphosis—a subject that Kish has always riffed on with her swelling list of talents. While her 2016 debut showcased the rapper’s conversational flow, Mothe sees Kish in a period of transition with her newfound singing voice taking center stage over hazy synths.

Between directing music videos and the launch of her new clothing label AGGY!, Kish took a break to discuss her intentions for Mothe, creative capacity and the role of spirituality in keeping her grounded.

AW: Now that Mothe is out, what have you been up to?

Yasmina Kahn

Yasmina Kahn is an American architect based in Los Angeles. She has collaborated with brands such as Stüssy and artists like Kilo Kish.

SOSUPERSAM

SOSUPERSAM is the moniker of professional DJ, danger, and businesswoman Samantha Duenas. She has released 2 EPs: Gardens (2016) and Priority (2018).

ComplexCon

Held in Long Beach, California, ComplexCon is a curated convention and music festival led by board members such as Pharrell Williams and Takashi Murakami. The convention showcases a curated variety of pop culture, art, food, style, sports, activism, innovation and education.

KK: I just finished the music video for “Void.” I’m debuting my new brand, AGGY!, at ComplexCon. I’m also working with Yasmina Kahn on figuring out the production side of performing Mothe live. Yesterday, I directed a video for my friend Sosupersam.

AW: Do you also direct your own music videos?

Elliot Sellers

Elliot Sellers is a director who has created music videos for the likes of Kilo Kish, Ty Dolla $ign, Cults and Lil Jon.

KK: I at least co-direct all of them, and I come up with the concept for most of them. Elliot Sellers and I worked on the “Void” concept together last year but didn’t have time to do it. We ended up putting it to “Void,” which is actually perfect for it.

I’m usually involved from top to bottom, in terms of color and the way I want my videos to look. I always do wardrobe, and I sit in on all the edits.

AW: You’ve spoken a lot about metamorphosis and how Mothe was a change in perspective from your last album. As an artist, your approach is very much about limitless evolution. Do you feel your personality morphs as well, or do you regard it as a constant?

KK: My perspective changed a lot. Reflections in Real Time had a lot of questions and internal dialogue. With Mothe, I wanted to overall feel freer, like I was coming through the other side of something. I tried to change the way that I saw and created things. I wanted it to be more organic and not overthink it, so I purposely set parameters within my own personality so I could stay open enough to create and perform it well.

My personality changed a bit, but there’s the constant wanting to top myself and being analytical about what could have been better or more interesting. My manager Justin says, “You’re one of those people that are never satisfied.” I can be satisfied with the fact that I achieved what I wanted, but there’s always another level.

AW: Was there a shift in your process?

KK: The process is pretty much the same. I wait until the title comes to me, and then I start working on it from there. I wait around and work on other stuff, and once I have a title, I go in and try to think of visual identity and do research. Then I do music after that.

“I wanted to overall feel freer, like I was coming through the other side of something.”

— Kilo Kish

I think I give all my projects an equal amount of energy and focus, but I don’t judge this as harshly as I would judge a record. With an album, I would focus a lot more on making sure the whole pallet is within the same vein. With an EP, it’s more about trying out ideas versus making something super solid.

EPs are also good bridges between two albums that are super different. They baby-step your listeners into another chapter. That’s what I choose to use my EPs to do.

AW: You mentioned how you always start with the title. It’s genius because then you don’t get bogged down by the minutiae of what the lyrics are going to be. You start at the top and work down.

KK: I like doing that personally, but I know so many people do it the opposite way. Then there are people who write and write endlessly, and when they find a vibe they curate a collection of music. But I don’t have a collection of music that hasn’t been put out. I don’t have 200 songs just chilling somewhere.

AW: You seem hyper-aware of your creative process and of not being intimidated by how hard that process can be. Is there any aspect of your art that seems to come especially easy?

KK: If something is not straight or a color is slightly off, it’s easy for me to notice. This actually causes me more problems than good because it becomes something I need to make sure gets fixed.

It’s also easy to create references because of the way I catalog information. I can be inspired by something I saw when I was fourteen and recall the details quickly. I’ll search it and show people like, “This is what I mean.”

Also just coming up with creative ideas is really easy, as well as making last minute adjustments. I’ve been DIY for so long that I pretty much learned how most industries work in the sense that I can draw from what I know to make quick changes and come up with creative solutions. If I need to make t-shirts or get a dress made, I can figure it out. The hard part can be bringing those ideas to other people, and depending on whether or not they agree it can become a problem in itself.

AW: Speaking of, do you look for specific qualities in the people you collaborate with?

KK: For me, it’s openness to do the unexpected or atypical. Also thoroughness. I’m super thorough in my research and detail-oriented, and I prefer to work with people who are extremely diligent in that as well because it makes everything easier. I know they’re taking as much care in the project as I am and have similar values in terms of wanting to push the boundaries.

With a lot of things there’s the possibility that “people will like it more if I do it this way” or “it’ll get more traction if I do it that way.” Also I could make more money if I were cutting corners in production. It really comes down to being on the same page and putting creativity before other interests.

AW: Do you feel it’s more beneficial as an artist to be humble or to be proud of your work?

KK: I think within our industry it may be better to be proud because if you’re too humble about your work then you won’t even put it out or believe it matters. You have to be the one who gives it value first, and then other people will then subsequently see it and give it value.

Philosophically speaking, it’s probably better to be humble because we’re in 2018. There is so much reference at this point that it’s really hard to make anything extremely unique. I can name so many references for everything I’ve done, and it’s not all musical. We can’t say that we don’t have banks and banks of reference when we have the internet. I think it’s better to be realistic about how much we’re actually adding.

“I think it comes down to not letting your ever-changing emotional state regarding your work get in the way of continuing to do it.”

— Kilo Kish

AW: That’s interesting because I know you really try to shut off too many outside influences when you make an album.

KK: Yes, but that’s just me. I’m very sensitive with what comes into my body. I can feel the difference between when my mind is overloaded versus not.

I have so many safeguards in the way that I work. I’ll plan a project two months before I work on it, and it probably won’t come out for another six months after that. I want to make sure everything actually happens and that I’ll have enough stamina since I do so much of it on my own.

AW: You do so many different kinds of art. When you have simultaneous projects, do you find yourself talking about the same themes? Or do you try to take a break in topics from one genre to the next?

KK: It carries through sometimes. For example, when I was doing Reflections in Real Time I also did a gallery show. The projects were unrelated, but the themes about social media and its implications carried through to the show.

When I do things close in succession, it can carry through. Which is why I won’t work on music right now while we’re working on stuff for Mothe. I don’t write or listen to that much music until I know I’m ready to start another album.

There are varying levels of total creativity amongst musicians. Some love to sit down every day and make a piece of music. Then they have other people collaborate with them on album artwork and videos, and they have a creative director to design their show space. But for me, I have to be all of those things, and I think a lot of indie artists are that way as well. It can be draining to do that while making a fashion brand at the same time. I try not to hold too much information at the same time.

I really believe that within your brain you have 100%. It’s not 100% to this and another 100% to that. You have 100% total. If you want to devote 50% to music and 50% to fashion—or 50% to music and 25% to your toxic relationship and 25% to whatever else—those are all depleting your total amount of energy. I try to conserve as much as I can.

AW: Would you ever produce music for other artists?

KK: I’d be quicker to work on videos or visual identities because I have no producing expertise besides what I’ve learned from working with my own producers. I sit in on sessions, and I give input when the beats are being made for my record, but being the producer is too many options for me. It’s soundbank after soundbank. Even when I make music, I get bored super easily. I can’t sit there for hours and hours listening to the same thing over and over.

I see myself more as a visual artist or a designer than a musician in the way I approach my music. I just happen to use the things I know from other things, and I’m able to make good music. But I think that the world of being a musician is super hard, and I don’t think I would ever be that great at making beats. I’ve tried, and I just don’t have the patience for it.

“There will be things that are the highlight in your life story, and other things will be a paragraph…It’s the body of work that’s important.”

— Kilo Kish

AW: It goes back to what you were saying earlier about how you like setting attainable parameters for yourself.

KK: It’s very hard not to have any parameters and to just have a blank piece of paper. People and brands are always like, “Do whatever you want!”

I’m like, “No, what are the actual parameters? What is the budget? How much space is there?”

These are important things to know so that I can even get started because “whatever you want” could mean anything in the entire universe.

AW: Do you have a favorite song on Mothe?

KK: I like “Like Honey” the most because I like the mix the most. It’s the closest to what I thought the project would sound like, but you never know until it’s done.

With Reflections, I tried super hard to achieve a specific idea, and then it was kind of achieved but also kind of not. With Mothe I learned to accept that the fun part of making music is not knowing what you are going to get.

AW: Anyone who’s been at something tenaciously for a while, such as yourself, must confront necessities like trial and error. How do you navigate discouragement or uncertainty?

KK: I can be very moody and artsy. I can be a martyr to my art. I can be obsessive. I can be very creative and purposeful. I think it comes down to not letting your ever-changing emotional state regarding your work get in the way of continuing to do it. One day you might have the best day of your life, and the next day you might be like, “I suck at everything.” I think that’s just being a creative.

At least I’m aware that it’s a tumultuous process. With the back-and-forth of emotional states and status—people either paying attention or not paying attention—there’s no way to do it and not have varying emotions. When you have the feeling of “I don’t know if I’m going to keep doing this,” the answer is always “yes.”

I’m probably going to be an artist forever. Even if I don’t always make music, I’ll find some other creative outlet, whether that be through brands or creative direction. I don’t necessarily have these goals of being an international pop star. I want all of my work to be good and to be impactful, and it’s a lifelong quest and project.

There will be things that are the highlights in your life story, and other things will be a paragraph. No particular project is going to be the one. It’s the body of work that’s important.

AW: That philosophy shows in how many different things you do.

You’ve collaborated with Childish Gambino, and he’s known to bury himself in his work and emerge with a finished project that makes people wonder how he finished it so quickly. Has that been your approach too?

KK: Donald and I are quite similar in that way. I used to be a lot more social when I lived in New York, but LA has a different way about it where you see people less than normal. I got used to not having my core group of friends out here and got super into my work.

It gives me a lot of purpose to wake up early. I’ll wake up, go for a walk, and get started immediately. I don’t stop until it’s at least dinner time.

“I needed something outside of our planet to latch back onto and to ground myself with again.”

— Kilo Kish

AW: You’ve mentioned a little bit in other interviews your spiritual background, which is interesting because in this industry not many people believe in or acknowledge spirituality as a facet of life, much less their personhood. Do you have a current practice or belief system that informs your art?

KK: Growing up in the South, I went to church every Sunday and was super Christian. Then I kind of didn’t do any of it when I moved to New York. I didn’t acknowledge that whole part of myself, or I guess I was just busy.

Then midway through making Reflections, I got really depressed. I think also just being twenty five, I had so many questions. It was bogging me down. I can go into bouts of existential depression just because I have thoughts that other people don’t necessarily talk about. At that point, I hadn’t expressed my questions through the album yet—I was in the process of doing that. I also was reading tons of weird philosophy books which can be quite dark. Life can be depressing if you are looking at from such a harsh perspective.

I think I needed something outside of what I was working on, outside of people. I needed something outside of our planet to latch back onto and to ground myself with again. I began going back to church a bit. It helped me to reground myself in a time that I felt really wiry and loose. I was doing fine from a career standpoint, but mentally I was spinning out a little bit.

Because it was so helpful, I’ve just continued. I continue to pray now and watch church stuff online and listen to music. I’ve gone to therapy before, and I’ve done so many different things for my own anxieties. But I feel that, at least for me, it aids in keeping me very balanced and grounded.

“It’s very hard not to have any parameters and to just have a blank piece of paper.”

— Kilo Kish

AW: Your stage presence is very expressive and reminded me of someone having a conversation with themself in the mirror. But how do you experience it?

KK: It’s fun to perform now. I didn’t used to like it that much because I wasn’t sure what vibe to put forth, and I wasn’t comfortable being myself. I was more so trying to make sure people thought I was nice or good. I also thought I had to be engaging in cliché ways. You go on stage and say, “How’s everybody doing tonight?” and “I hope everybody’s feeling alright!” It felt really uncomfortable because I don’t like small talk.

It’s also fairly recent that I sing. Being a perfectionist, I was worried about, “What if the notes aren’t exactly right?” I had to look at it from the basis of conceptual art, and once I applied what I knew about art to the musical performance space, it got a lot easier.

Now I don’t judge each performance on whether it’s the best representation of who I am—it is always the best representation of who I am because I’m doing it. It’s easier now that I’ve changed my perspective. I’m able to be that angsty teenage part of myself on stage all of the time, which is fun.

AW: What did your younger self want to be?

KK: I wanted to be a chef when I was a kid. Then I wanted to be an architect, which is what I thought I was going to go to college for. I did a pre-college program at Pratt and realized that I’m the worst at ruler-based things. Then I went to college to be a fashion designer.

When I was a teenager, I had a jewelry company and would screenprint shirts with stencils to sell to my friends. I had a fictitious name I filed when I was fifteen or sixteen.

AW: So entrepreneurial so young.

KK: There was that company where kids created cookies that were sold in the mall. Do you remember that?

AW: I forgot about that! They were so cool.

KK: To me that was being entrepreneurial. I was like, “He’s sixteen, and he has a company already!” I was already being judgy to myself very young.